The Perilous Freedom of the Fringe

For those who find themselves disenfranchised by the political mess of the Left, Right divide in Western politics.

There is a particular kind of exhaustion that defines political life in the 2020s. It is not the weariness of the partisan, drained from the exertion of fighting for a cause they believe in. Nor is it the simple apathy of the disengaged. It is a more corrosive fatigue, a quiet, grinding disillusionment felt by those who find themselves standing on the political fringes, not by choice, but by intellectual exile.

This is the strange and unenviable position of the politically homeless. To be on the fringe in our era is not necessarily to subscribe to some radical, esoteric ideology. It is, more often than not, simply to possess a functioning memory and a preference for intellectual consistency; it is to look at the grand platforms of the Left and the Right, and even the supposedly sensible Centre, and to find in all of them a series of profound and often insulting contradictions. It is to feel like a man without a country in the very land of your birth.

It's pretty bleak. On one side, we are offered a politics of pure sentiment, a therapeutic vision of governance that often seems to view the state as a tool for validating identities and prosecuting historical grievances, all while the mundane, essential functions of a thriving society—safe streets, solvent public services, a dynamic economy—are treated as secondary concerns, if not outright distractions. On the other hand, we are presented with a reactionary carnival, a politics that fetishises the symbols of a lost golden age but offers little in the way of a coherent philosophy for traversing the intricacies of the present, often descending into a crude nationalism that is as intellectually vacant as it is emotionally potent.

And the centre? The great, sensible, moderate centre has abdicated its role. It has become a space not of conviction, but of calculation—a triangulation of focus-group-tested platitudes designed to offend the fewest people possible. It offers no grand vision, no inspiring alternative, only a managerial competence that seems utterly inadequate to the scale of the crises we face. It is a political home for those who wish to be governed by spreadsheets, not by ideas.

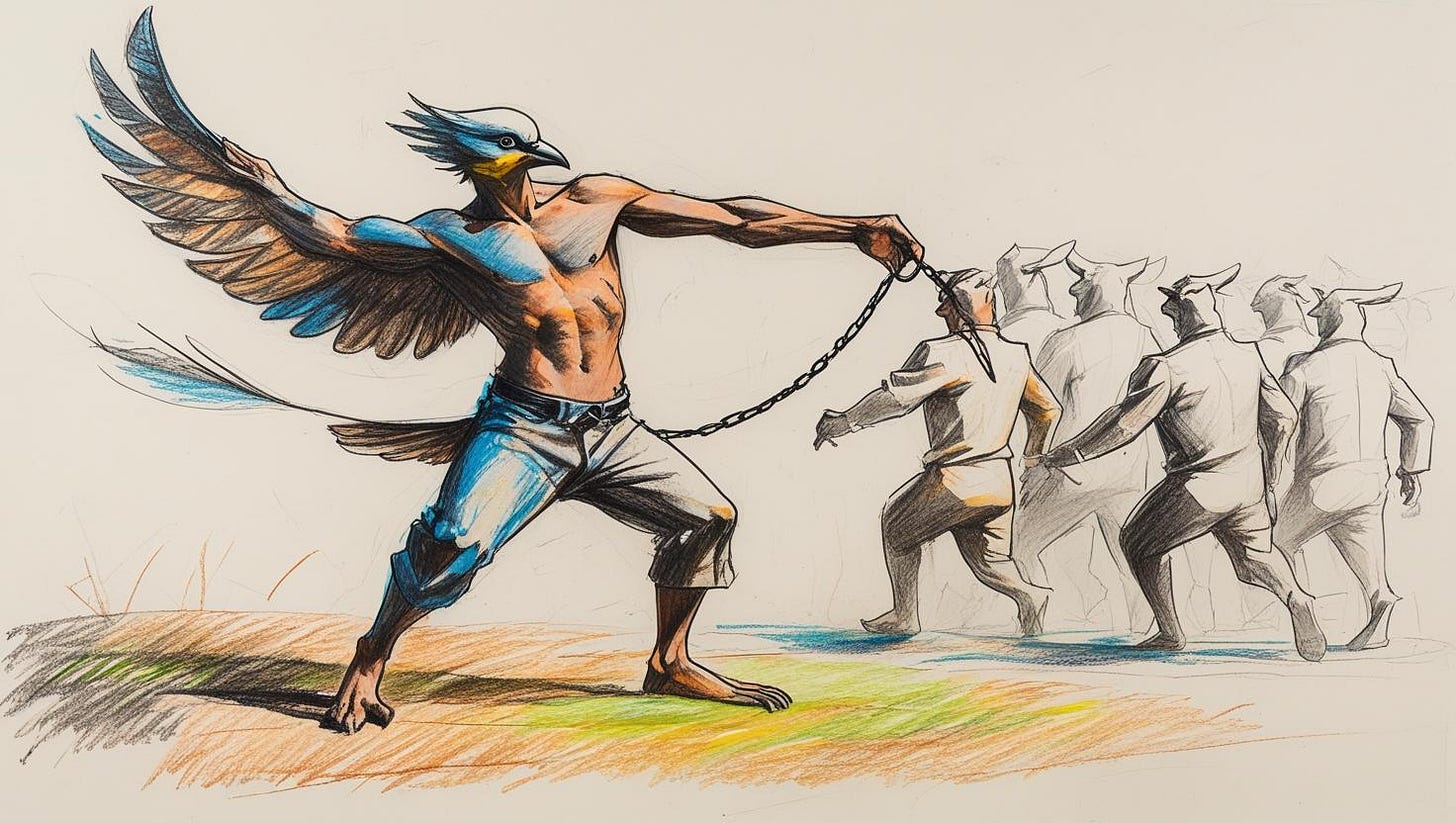

So, what now? If the established political tribes offer no shelter, is there any recourse but to chronicle the journey downwards? This is the central question for the citizen on the fringe. It is a question that carries with it both a heavy burden and a perilous kind of freedom.

To be politically homeless is to be untethered, and while this brings a certain vertigo, it also offers a unique and powerful perspective. The citizen on the fringe, freed from the obligation to defend a party line, is uniquely positioned to practice a more honest form of civic engagement. But this requires discipline. It requires a conscious rejection of the intellectual habits that define our broken political discourse.

First, we must insist on the sovereignty of the individual mind. The primary error of modern politics is the insistence on the ideological package deal. To get sensible economic policy, one is told one must also accept a host of social dogmas one finds repellent. To stand for traditional values, one must apparently swallow a foreign policy of reckless adventurism. This is a false choice, a loyalty test designed to enforce tribal cohesion at the expense of reason. The first duty of the fringe dweller is to dismantle these packages. It is to say, without apology: I will take the sound ideas from the Left, the sound ideas from the Right, and I will discard the nonsense from both. This is not indecision; it is intellectual integrity.

Second, we must elevate principles over personalities. Our political sphere has become a theatre of celebrity, a cult of personality where leaders are treated as avatars for our hopes and hatreds. This is a catastrophic misreading of the purpose of politics. The fringe dweller must develop a deliberate detachment from this spectacle. Instead of asking, 'Whose side are you on?' the more vital question is, 'What do you believe?' The goal should be to build one’s political identity on a bedrock of enduring principles—free speech, fiscal prudence, equality under the law, the preservation of the natural world—rather than on the shifting sands of allegiance to a flawed and transient political figure.

Third, we must embrace the virtue of political humility. A functioning society requires compromise and an acknowledgement that one’s opponents are not always acting in bad faith. The partisan sees the world in stark binaries of good and evil; the person on the fringe has the luxury of seeing in shades of grey. This means accepting the discomfort of nuance and the reality that there are no simple solutions to complex problems. It means being willing to say, 'I don't know', three words that would revolutionise our entire political culture if uttered more often by those in power. It means recognising that the work of a good citizen is not to have all the answers, but to ask the right questions.

Finally, we must rediscover the power of the local. While the national stage becomes ever more a forum for performative outrage and ideological warfare, it is often at the regional level—in our towns, our cities, our school boards—that real, tangible change can be effected. Engaging with the politics of one’s own community is an antidote to the sense of powerlessness that the national discourse engenders. It is a way to practice a politics of practical problem-solving, rather than one of abstract ideological combat. It is, in short, a way to build a home, even when the national house is in disarray.

None of this is easy. To stand apart from the tribes is to invite scorn from all sides, to be labelled a traitor by the partisans and an eccentric by the indifferent. It is to accept an inevitable loneliness as the price of intellectual freedom. But the alternative—to submit one’s conscience to the custody of a party, to parrot slogans one does not truly believe, to participate in the slow, managed decline of public reason—is far worse.

The political fringe, then, is not a barren wasteland. It is, or it can be, a frontier. It is the vantage point from which the pathologies of our politics are most clearly seen, and the space where a new, more durable form of citizenship can be forged. To be politically homeless in a time of madness is not a sign of irrelevance. It is a sign that you are still listening, still thinking, and still holding out for the possibility of a better country.

And in this unthinking age, that may be the most radical political act of all.