The Uncomfortable Inheritance: Faith, Secularism, and Britain’s Asymmetrical Piety

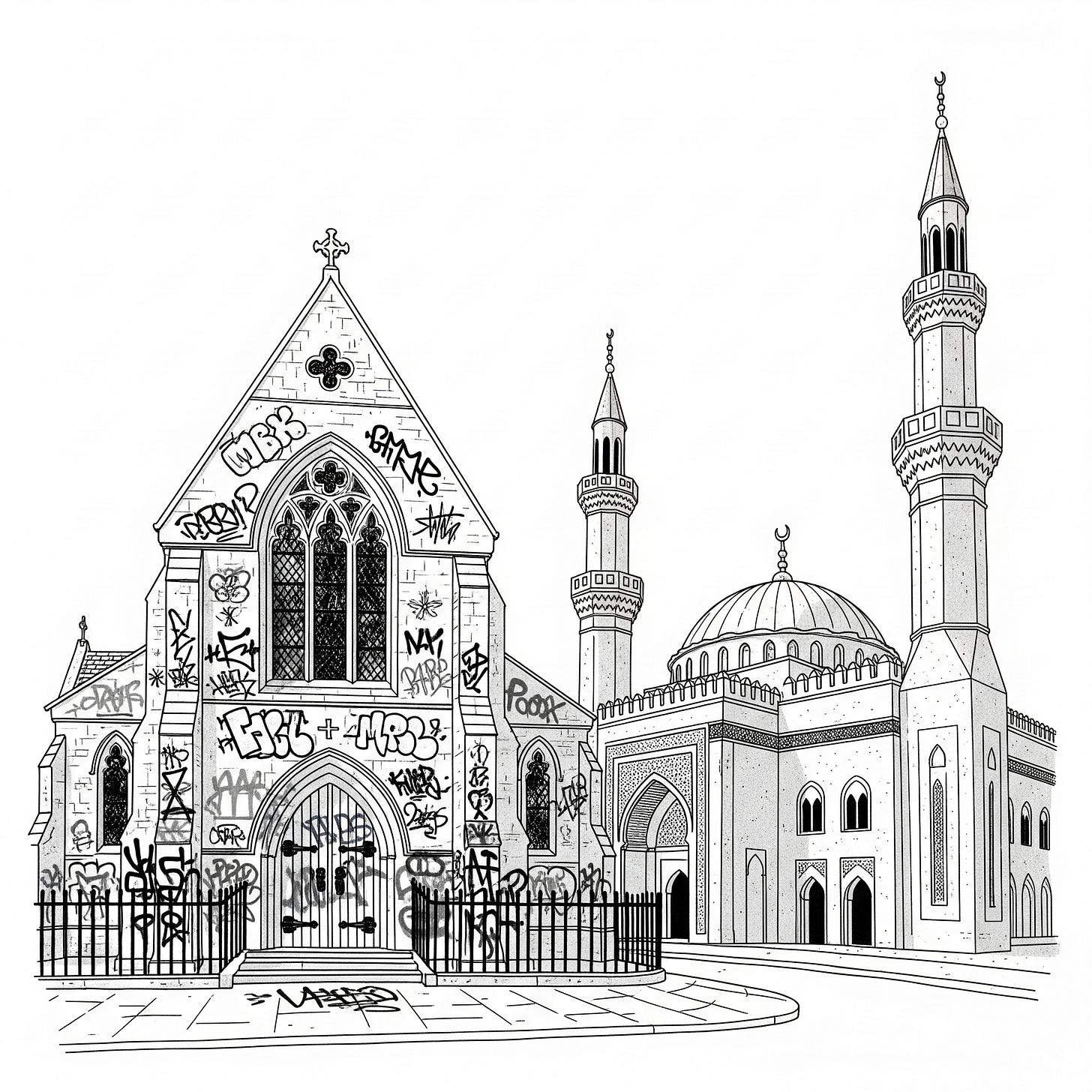

A nation’s relationship with its gods is rarely a simple affair, least of all in a country like Britain, which imagines itself to be largely post-religious. It is a land of quiet but profound paradox. Its great cathedrals stand as monuments to a faith that now struggles to fill provincial village pews; its skylines are punctuated by the minarets of mosques, symbols of a vibrant, living belief that is often viewed with a unique and anxious suspicion. The tolling of a church bell is the sound of heritage, a piece of the national soundtrack. The call to prayer, for some, is an intrusion. Within this dissonance lies a critical pathology of the modern British state: a nation that believes itself to be secular, yet remains haunted by the ghosts of its religious past and confounded by the demands of its multi-faith present.

To observe the public discourse surrounding the Abrahamic faiths today is to witness this condition acutely. There is a consequential asymmetry in their public treatment, a deep imbalance that gnaws at social cohesion and risks corroding the very foundations of the democratic, secular ideal the United Kingdom purports to champion. This is not the product of a grand conspiracy or a deliberate policy of state. It is a quiet, creeping condition, born of historical inertia, demographic anxiety, and a fundamental confusion about what secularism ought to mean in the 21st century.

The first component of this diagnosis concerns the strange inheritance of the nation’s primary faith. Christianity, and the Church of England in particular, exists in a state of being both officially enshrined and culturally disposable. It is the ghost in the machine of state—its bishops are granted seats in the House of Lords, its prayers frame the opening of parliamentary proceedings, and its most sacred rituals are inseparable from great moments of national life, from a coronation to Remembrance Sunday. This is the architecture of an established church.

Yet, it is this very residual privilege, this institutional familiarity, that renders it uniquely vulnerable. To critique or even satirise Christianity in modern Britain is a culturally sanctioned act. It is seen not as punching down at a vulnerable community but as speaking truth to a fading power, a pillar of an old establishment. Works like Monty Python's Life of Brian or the novels of Philip Pullman can enter the cultural mainstream and be celebrated as vital critiques of dogma, their blasphemy insulated by the perceived safety of the target. The faith has become a kind of public utility, expected to be there but open to constant complaint, its iconography and tenets treated as common property to be repurposed for art, comedy, or scorn without significant social or legal consequence. It is a victim of its own lingering prestige.

In stark contrast, the nation’s other major Abrahamic faiths, Judaism and Islam, are handled with a markedly different caution. This caution is often perceived by critics as a form of preferential ‘protection’, an invisible shield that deflects the kind of scrutiny Christianity endures. But this reading is too simplistic. This is not a matter of arbitrary favouritism so much as a complex and anxious societal defence mechanism, rooted in traumas both historical and contemporary.

Judaism in Britain exists in the long, dark shadow of the Holocaust. For centuries before that, it was the faith of a people subject to pogroms, expulsions, and systemic antisemitism across Europe. Islam, meanwhile, has become, in the post-9/11 era, inextricably linked in the public imagination with terrorism and geopolitical conflict. Consequently, any public critique of these faiths’ theologies or practices is immediately complicated by the distinct bigotries of antisemitism and Islamophobia—prejudices directed at people, not just ideas. The line between a legitimate critique of religious doctrine and a dangerous incitement of racial or ethnic hatred is fraught with peril. The resulting public reticence is therefore not a shield for the faiths themselves, but a necessary, if sometimes clumsy, bulwark to protect their followers from harms that are not historical artefacts but urgent, present-day realities.

Here is the great and terrible irony for a secular state. This asymmetry, born of comprehensible historical and social forces, creates a deeply unstable equilibrium. It is corrosive because it denies the existence of a common ground for debate. Instead, it fosters a tripartite problem. First, it allows a potent grievance narrative to fester within the majority, a sense that its own heritage is uniquely and unfairly exposed while others are sacrosanct. Second, in its admirable desire to protect minorities from bigotry, it risks chilling legitimate, necessary critique of all religious doctrines, conflating the vital work of questioning ideas with the vile act of persecuting people. Third, and perhaps most dangerously, it encourages a competitive victimhood, where faiths are incentivised to catalogue their injuries and broadcast their vulnerability rather than participate as equal, robust partners in a shared civic space.

The ultimate risk is not that one religion will triumph over the others in a battle for supremacy. The risk is the degradation of the secular principle itself. A truly secular nation does not operate by curating a hierarchy of respect based on a faith’s historical dominance or its contemporary fragility. It operates on a single, unwavering principle: the freedom of individuals to believe, or not believe, coupled with the freedom of all to question, critique, and even satirise any and all ideas—religious or otherwise—without fear of state-sanctioned reprisal or societal intimidation.

The current arrangement, however well-intentioned, fails this test. It has mistaken the laudable goal of protecting people for the untenable project of protecting their beliefs from challenge. We did not arrive here by decree, but by a slow, unthinking drift, and the institutions of the 21st century only accelerate the process. The digital public square, with its algorithms designed for outrage and its flattening of context, amplifies every grievance and widens every fissure. Nuance is a liability.

The question for the United Kingdom, then, is not how to better ‘manage’ its faiths as if they were competing corporations. It is how to rediscover a form of secularism robust enough to treat all ideas with equal scrutiny while treating all people with equal dignity. At what point does the careful navigation of sensitivities become a quiet surrender of the principle that, in a free society, no belief can ever be placed beyond the reach of question?