The Uniform of Righteousness

Challenging the intoxicating rush of the modern person to reach the moral high ground.

This piece was inspired by Tim Syrek’s sharing of a haunting quote by Karl Stojka, a survivor of Auschwitz:

‘It was not Hitler or Himmler who abducted me, beat me and shot my family. It was the shoemaker, the milkman, the neighbour, who received a uniform and then believed they were the master race.’

We find it easy to condemn the architects of history’s horrors. Hitler, Himmler, the names that sit in the dark recesses of the 20th century, serve as convenient gargoyles. As long as we believe evil is something found only in the grand, sweeping gestures of dictators, we feel safe.

But Karl Stojka, who survived the depravity of Auschwitz, didn’t leave us that luxury. He didn’t point his finger at the high command. He pointed it at the milkman. He pointed it at the neighbour.

His point was simple: the machinery of oppression doesn’t run on the whims of a few madmen; it runs on the enthusiasm of ordinary people who are suddenly told they are better than their neighbours. All it takes is a uniform—physical or ideological—and the belief that they are the arbiters of who belongs and who does not.

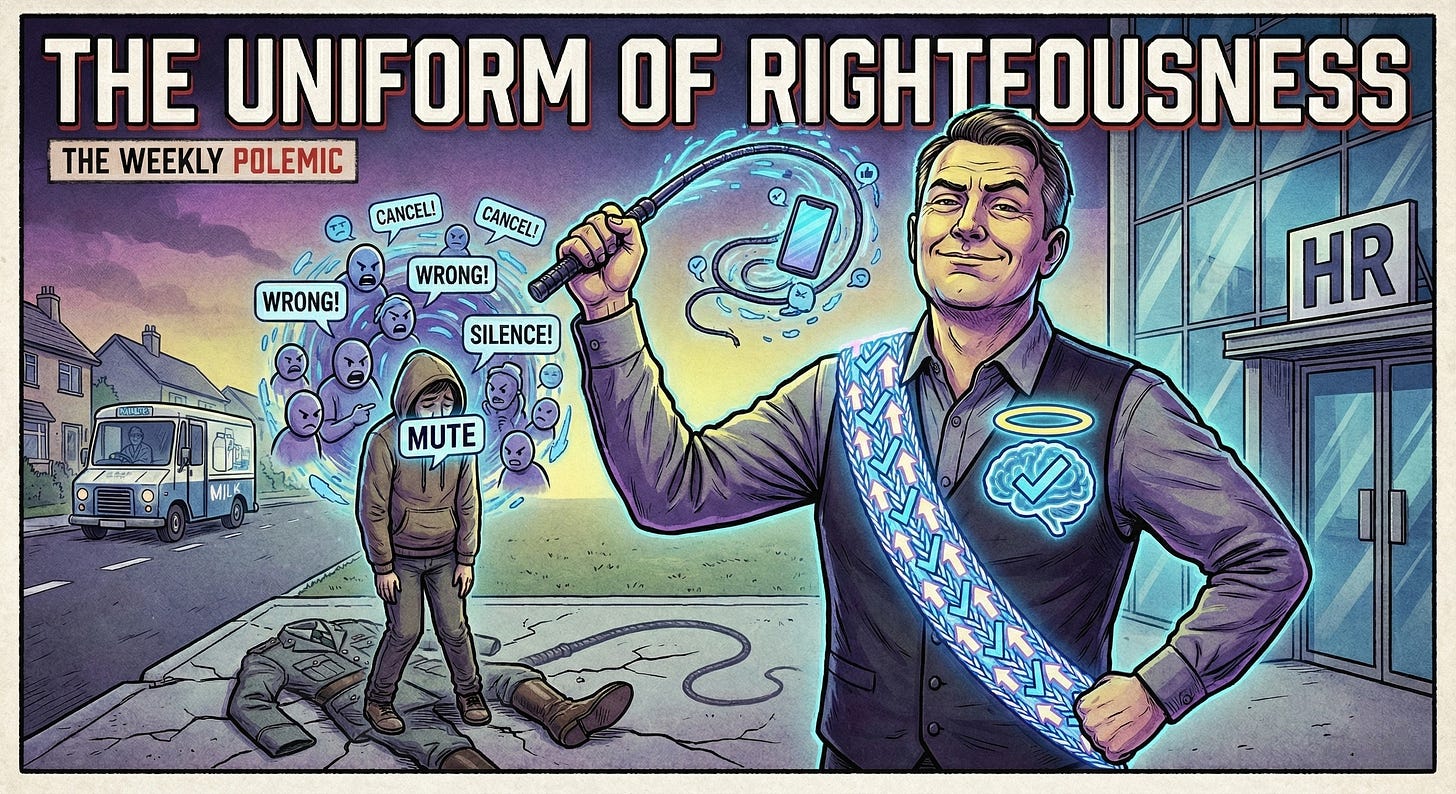

Today, the uniform has changed. It isn’t made of grey wool or leather boots. It is woven from the threads of moral superiority and ‘correct’ thinking. We are seeing a resurgence of the very impulse Stojka described: the belief that holding the ‘right’ views grants one the authority to silence, beat down, and socially abduct those who don’t conform.

We see it in the HR manager who treats a private opinion like a forensic crime. We see it in the university administrator who looks at a dissenting professor not as a colleague to be debated, but as a contagion to be removed. These are the modern shoemakers, ordinary people who have been handed a digital badge and told that their intolerance is actually a form of kindness.

The milkman of 2026 doesn’t need to wait for a government decree to start the abduction. All he really needs is a stable internet connection to a smart device. And, let’s be honest, there is an intoxicating, almost narcotic rush in being the one to call out a neighbour.

It’s the person who spends their evening trawling through ten-year-old tweets to find a reason to destroy a career.

It’s the student who records a lecture, not to learn, but to find a gotcha moment that can be used to humiliate a teacher.

It’s the friend who quietly unfollows and blacklists you, not because you’ve done something wrong, but because you dared to ask a question that made them uncomfortable.

When you believe you represent the pinnacle of moral thought, a sort of intellectual master race, you no longer need to listen to the person next door. You only need to correct them or delete them.

The most terrifying part of Stojka’s observation is, perhaps, how quickly the neighbour turns. The transition from ‘the person who shares my street’ to ‘the person who must be purged’ is remarkably short when fuelled by a sense of righteous mission.

We see it in the glee of the digital mob, and we see it in the shutting down of discourse on campuses and in public squares. It is the same old human rot: the intoxicating rush of being the one holding the whip, rather than the one under it.

If we lose the ability to speak freely—to disagree, to offend, and to be offended without seeking the destruction of the other—we aren’t really protecting society. We are merely putting on the uniform Stojka warned us about.

The lesson from Auschwitz isn’t just ‘never again’ to the gas chambers; it is ‘never again’ to the mindset that your neighbour is your inferior because they lack your specific brand of enlightenment.

True liberalism, I believe, is found in the grit of open debate, not the silence of the cemetery. If we want to honour the memory of people like Karl Stojka, we must stop looking for the next Hitler and start watching the person who thinks their ‘correct’ opinion gives them the right to play the master.

Having said all of this, I’d be remiss to not offer a few suggestions on how to fix this growing issue. So, let’s give that a go.

If the path to tyranny begins with the neighbour putting on a uniform, the path back to a sane society must begin with the individual refusing to wear it. With that, I should add that the political pendulum always swings too aggressively from left to right. Remember, first and foremost, that de-escalating this ideological arms race does not require a grand political movement; it requires a quiet, personal rebellion against the urge to be ‘right’ at the expense of being human.

Before you hit ‘send’ on a scathing retort or join a digital pile-on, ask yourself: Am I trying to solve a problem, or am I just enjoying the feeling of being superior? If it’s the latter, you have just put on the milkman’s boots.

The modern enforcer assumes that any disagreement is a sign of hidden malice. Break the cycle by assuming your neighbour is simply coming from a different set of life experiences. Most people aren’t evil; they are just as worried and confused as you are.

You do not have to agree with someone’s opinion to defend their right to have it. When you see a neighbour being mobbed for a dissenting view, standing up for them, even if you disagree with their premise, is the ultimate act of de-escalation. It signals that the relationship is more important than the ideology.

In a world of shouting matches, curiosity almost feels like a superpower. Instead of correcting, ask questions. It is much harder to abduct and beat, metaphorically or otherwise, someone when you have taken the time to understand why they see the world the way they do.

My parting message to you, friend… We have to decide what we value more: the temporary high of moral victory, or the long-term peace of a community where the shoemaker and the milkman are just people again, rather than self-appointed masters.