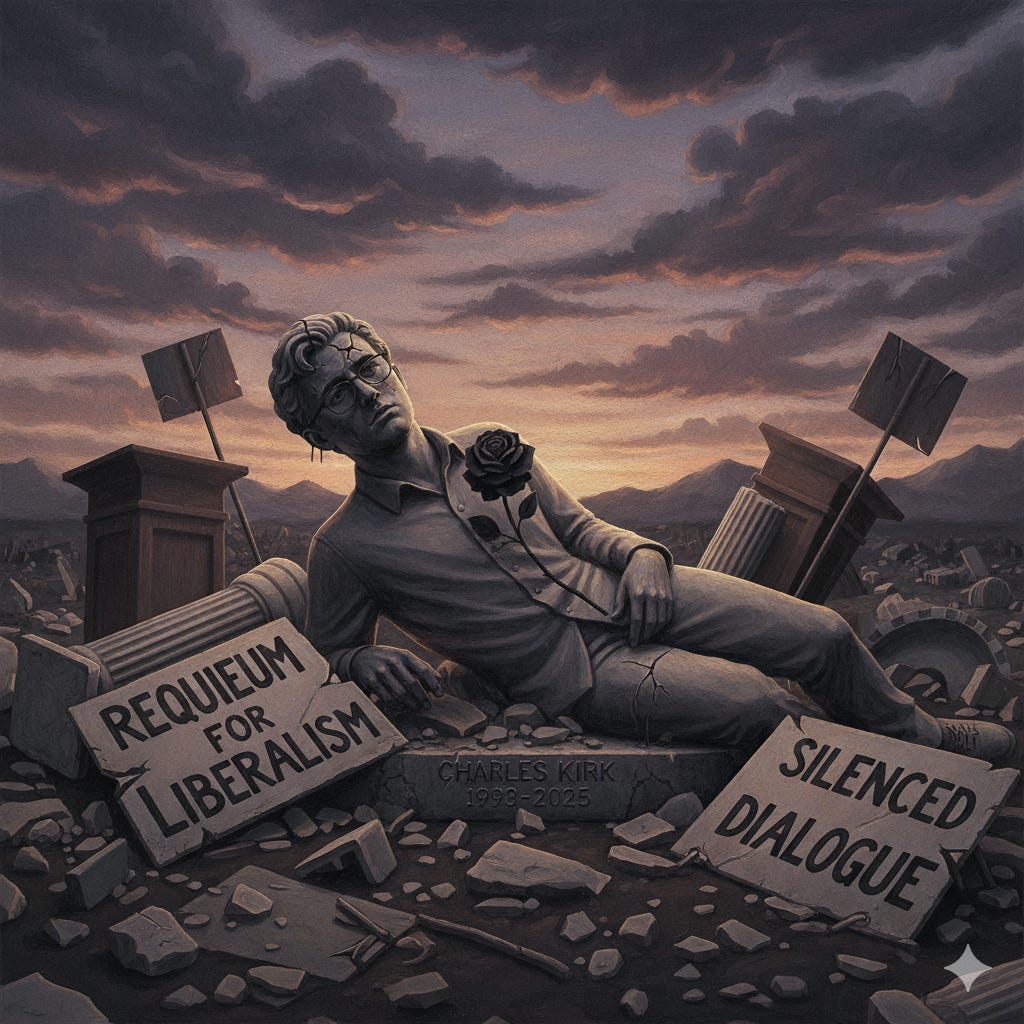

The Void, The Chorus, and The Intolerable Man

Contemplating the death of Charles (Charlie) Kirk and its wider implications for liberalism and the tradition of civil discourse in Western society.

To measure the legacy of a man like Charlie Kirk solely in terms of simple political wins or losses would be to misunderstand his project fundamentally. He was not merely a commentator; he was a man who chose to enter the storm. His passing has unleashed a predictable maelstrom of digital ephemera—the algorithmically-sorted tributes and condemnations. Yet, to focus on this frantic, reactive theatre is to miss the terrifying silence he sought to address. Kirk’s true legacy is not defined by the noise surrounding his death, but by the cultural void he bravely attempted to span.

He was, in essence, a man who believed in the power of conversation. In a West increasingly untethered from shared purpose, he toured the university campuses of the United States with a seemingly simple mission: to encourage civil discourse. This mission, however, was predicated on an idea that has now become dangerously obsolete: the existence of a shared reality. He operated as if two people could still stand on a common ground of observable facts to hash out their disagreements. The immense traction he gained was a testament to our profound intellectual and spiritual poverty; he found a desperate audience because the institutions that once fostered debate had abandoned their posts, leaving a vacuum of meaning. His work became a flashpoint where the irreconcilable realities of our fragmented age collided.

This explains, in part, the grotesque celebrations of his detractors. In the digital town square, those who fashion themselves as the guardians of liberal values have revealed a questionable—chilling, even—pathology. The response to Kirk's death has been a chorus of undisguised glee, a ghoulish spectacle of pronouncements that he ‘deserved it’. Herein lies the profound irony: in their rush to celebrate the demise of a man whose stated goal was public conversation, these champions of progress have embraced a logic that is fundamentally fascistic. (Oops, there we go again.) To celebrate the death of someone who merely sought debate is to trade the difficult work of argument for the cheap, tribal thrill of eliminating an opponent. This is not liberalism; it is a morbid inversion of it.

This reaction is more than just a distasteful lapse in judgement. It is, I would argue, a symptom of a catastrophic paralysis. A culture that cannot agree on the basic humanity of its political opponents is a culture that cannot solve any serious problems. Every issue, from fiscal policy to public health, is subsumed by the culture war, where the debate is no longer about the merits of an idea, but about the supposed moral failings of the person proposing it. The ghoul's chorus is the ultimate expression of this decay: a declaration that the person is the problem, and their removal is the solution.

The detractors, in their morbid victory lap, defined themselves in opposition to Charlie. He was their perfect antagonist, the figure required to sustain their own sense of righteousness. With him gone, they face a strange vacuum, for their enemy was not just a person, but a principle—the very idea of engagement. It seems to me that, in this hyper-partisan environment, the most hated figure is not the most extreme radical. Instead, it is the intolerable person: the one who refuses to surrender to the logic of one tribe fully. By saying ‘let's talk’ in the middle of a screaming match, he becomes a traitor to all sides, and the one everyone wants to silence first, because his very presence is a rebuke to their hysteria.

The machine, however, does not stop. The void remains. Charlie Kirk was a man who tried to speak into it, and the vitriol he received, both in life and in death, serves as a grim barometer. It suggests we've moved past political disagreement and into a state of cold civil war, where the goal is no longer persuasion, but elimination. The ultimate questions, then, are not about the legacy of one man, but about the survival of a society.

When dialogue itself becomes intolerable, who will dare to try next? And can a civilisation endure the death of its own conversation?